That Dragon, Cancer is not a game I want to talk about in relation to how it works. It demands a kind of attention different to that of mechanical analysis, sarcastic remark or theoretical conjecture. That Dragon, Cancer is about real people. Its subject, Joel Green, is a boy that died of cancer at the age of 5. The game that he sparked is, in its essence, the living diary of his parents – stark, terrifying & beautiful.

This morning, I watched a few videos about the game. I want to note a few things.

IGN published a video review of the game which I refuse to link. Whilst generally positive, it noted a few mechanical flaws – that certain sections of the games are ‘clunky’. There is an obvious moral criticism that we can make – it is somewhat insensitive to criticise a tribute to some1’s son for being imperfect. However, this hints toward something more important about how we view videogames, in part to do with the facile nature of the videogame press. To put this simply: no1 criticises the sentence structure of Anne Frank’s diary. Not only is it clearly insensitive, we do not consider her writing to be an object of entertainment. Morality may be suspended in the instance of videogames: we think of them as toys, no matter what they discuss.

A slightly more reflective piece by “Satchbags Drake” uses That Dragon, Cancer to reflect upon the idea of purpose, specifically on the manner in which Ryan & Amy Green (Joel’s parents) reflect on religion in the text. The same problem arises, however, from Drake’s analysis. His video sets videogames on a plane of “pure” artistry. In some ways, this is more complex to explain. There is no gross criticism, but an attempt to place the game in the realm of “high-art”. Drake poses the question of what the game means in an abstract, wholly textual sense.

Videogames can be entertainment, they can be “high-art”. Often these 2 (essentially trite) categories interact in complex ways. Whilst it must be clear that I do not wish to detract from the game’s artistry – it is incredibly poetic – the application of these categories entirely misses the point. That Dragon, Cancer has done something incredible. It has brought the medium of videogames, all too horribly, into a place that other mediums have stood before. That Dragon, Cancer has destroyed the notion that a videogame must be, primarily, a commerical product. Videogames are free to simply be texts.

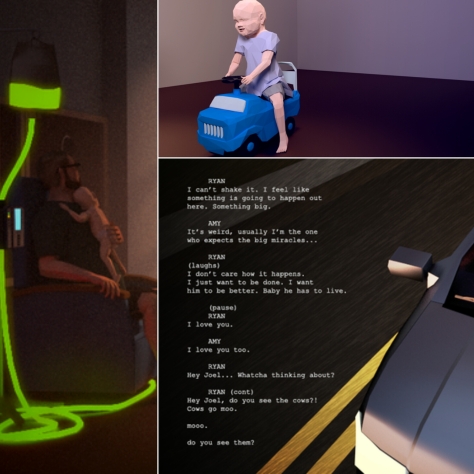

The only comparable predecessor to this game is 1 that I’ve written about before: Depression Quest. Depression Quest was an honest, brutal exposition on the subject of, well, depression. However, it failed to manage the same transformation achieved by these blocky images. Depression Quest hid behind artifice. It used fiction & a system of player agency to communicate its central messages. It did so in an incredibly effective way. That Dragon, Cancer does no such thing. There is no agency. Here’s the difference: That Dragon, Cancer is not about a theme, it has no message. It is about a real person. At the end of the game, Joel Green will still be dead.

‘What could we even say? He loved bubbles?’ This is a quote from a blog by Joel’s mother, Amy, titled ‘Pancakes for Dinner: Summarising a Life Cut Short‘. The title is important. Pancakes are not a metaphor. They were Joel’s favourite food. The defence of videogames as a medium does not require simply the defence of videogames as art. It requires much more. It requires a defence of the fact that videogames may do anything that any other medium may do. What is different is merely that we act in a videogame with agency. We do not consume passively. So, Joel is real to us too.

In the game’s development Joel’s father, Ryan, repeatedly articulated that 1 of the central concepts of That Dragon, Cancer was that videogames allow us to dwell. They allow us to live in spaces & with people that time has eradicated. They allowed the Greens to grieve, in a way that no other medium can. There is a scene in the game which allows us to read many of the messages of parents that have experienced the same tragedy as the Greens. It is heartrenching.

Here is the only symbolic meaning I will take from That Dragon, Cancer: this scene is an invitation to grieve with the Greens. I did. I wept because a human life was ending. & that means a lot.